In brief

I used to hate typing. I was very very slow, and the idea of touch typing, especially while coding, seemed impossible to me.

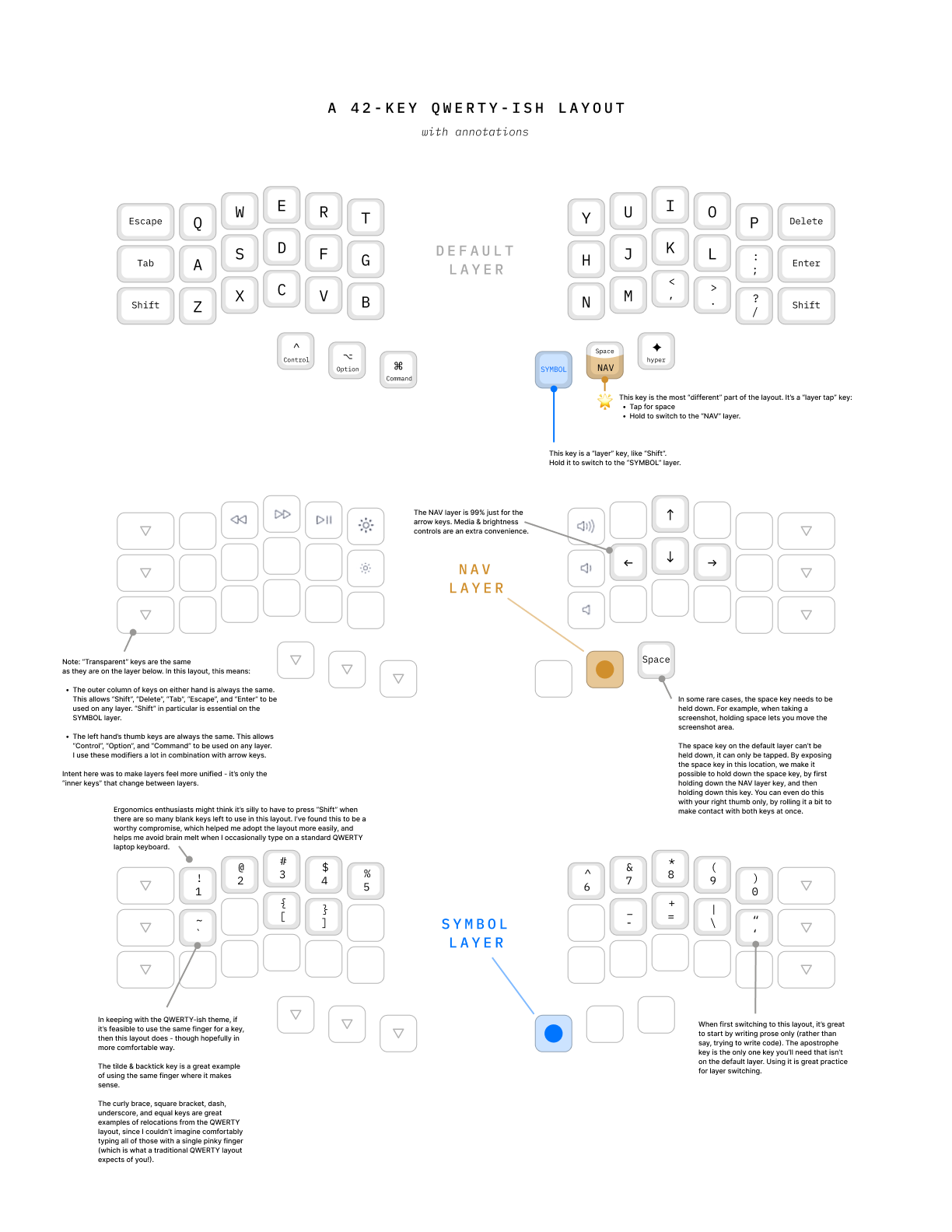

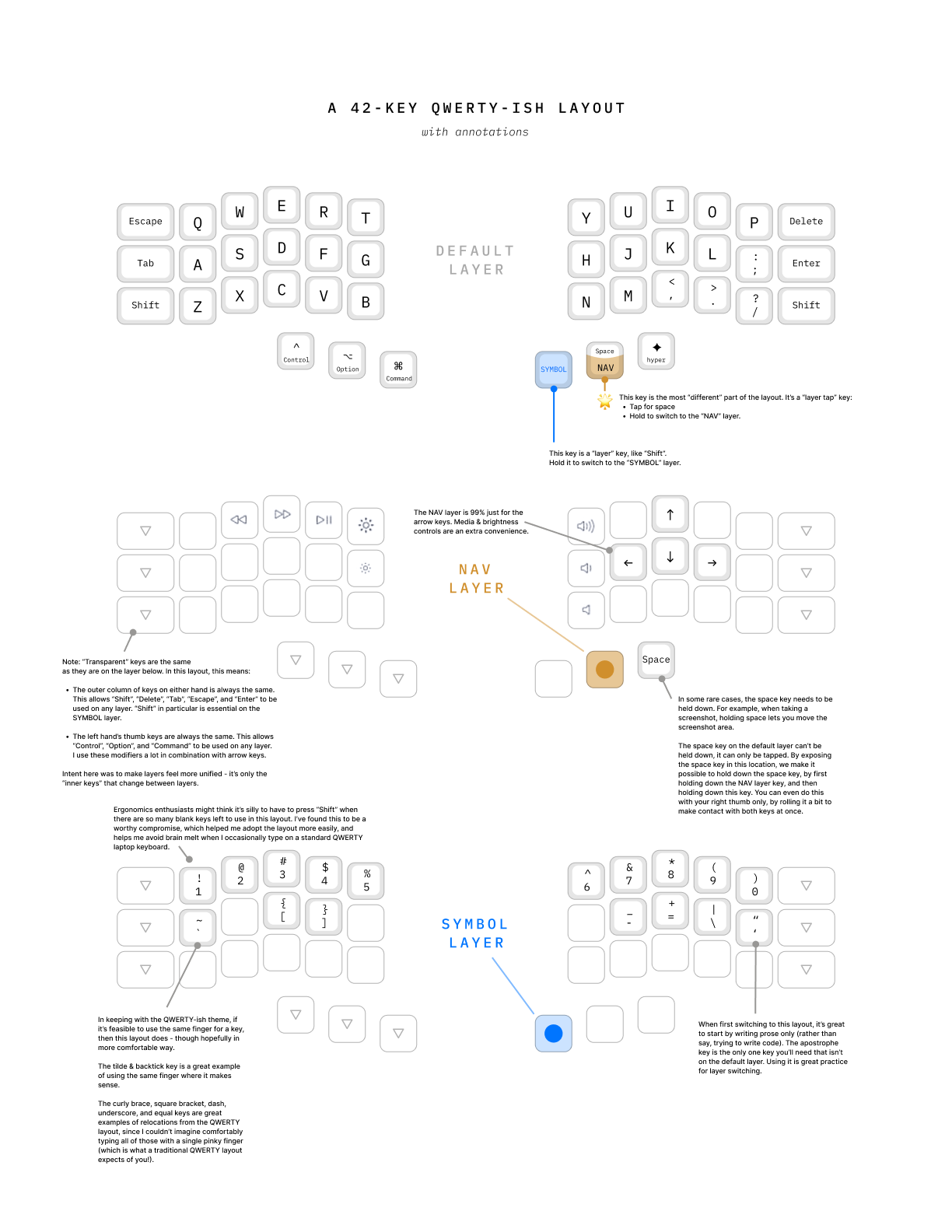

Now I hate typing and am slightly faster. I have weird modifications on my laptop keyboard. Also, I try to convince anyone willing to listen that standard keyboards kind of suck for human hands, and that if you hate typing too, it might be worth trying out a keyboard with 42 keys, with 20gf switches, with this layout:

Couldn’t be more straightforward, just a simple ol’ diagram with some brief annotations. Even so, I think the pain of switching keyboards will feel pointless unless you have context on why you might want to do it. With this in mind, please enjoy the long rant and my keyboard life story that follows 💖

Why bother?

If you’re anything like me, having someone be like “try this thing, it’s so good” tends to inspire equal parts of excitement and skepticism. Why can’t we just be happy with what we have? Why do we have to make everything complicated?

On the surface, a keyboard with only 42 keys sounds pretty annoying to work with, and compared to traditional keyboards, it seems like a very arbitrary limitation. It’s definitely kind of annoying to learn, so I figure a pitch for going through this pain is in order.

I think there are a few things that, for me, have felt inherently nice about this type of layout, which are worth explaining as a way to build motivation. These thoughts helped me stay relaxed, calm, and committed (mostly 😬) as I tried to figure out whether this weird nerd keyboard was my thing or not.

Why so few keys?

Why 42 keys? Because it makes it easier to touch type.

This might seem unintuitive. But I think it’s important to back up and ask: why do traditional keyboards have so many keys?

Why so many keys?

The Apple Magic Keyboard I used to type on has 78 separate keys, and it’s considered compact. A more common number of keys is 104. Why these numbers?

I’m taking a guess here, but I’m pretty sure it’s because in the analog world, each key’s functionality was limited by physical constraints. In its simplest form, a single key on a typewriter corresponded directly to a single symbol, to be stamped out by a little bit of metal.

The introduction of the Shift key made typing with a broader range of symbols possible, while keeping the number of separate keys manageable. It did this by adding a second physical layer of symbols, so that each key could type two symbols when “shifted” to this new layer. But, it’s difficult to design a keyboard or typewriter that has more than two physical layers. So in most typewriters, each key is responsible for at most two keys.

We’ve carried this through directly into computer keyboards, with the number of keys on a traditional keyboard being decided primarily based on this “one key, two symbols” responsibility. We even manufacture many keyboards around this limitation, with electronics, bubbly silicone blister designs, and the simplest possible wiring, all of which greatly cut costs, but further entrench this “one key, two symbols” constraint.

In other words, if a keyboard needs to be able to type more symbols, we’re in the mindset that we need to add more keys. Removing keys without removing symbols seems impossible, or at least, like it would break our mental model for how keyboards work. Which is perhaps why a 42-key keyboard seems so intimidating. This mindset is very valid, but is also a bit of self-imposed constraint, and we should consider why we’re imposing it on ourselves.

Why is typing so hard?

Have you ever sprained your right pinky trying to touch type brackets? Or strained to reach the number row without moving your hands too much? Or cursed yourself for your inconsistent approach to the 5 and B keys?

I started thinking about keyboard design constraints after I formally switched from designing to coding. I’d never learned to touch type, and it had always kind of haunted me. I’d always reassured myself that it made no sense for design work - I usually have one hand on a mouse, there’s no way I’m going to learn to touch type with one hand.

But for coding, I felt like I didn’t have an excuse. It seemed like something I should learn how to do, that everyone else seemed to have learned how to do… and yet whenever I tried to learn, keyboards still didn’t feel like they were designed for me, or anyone with two hands and five fingers, really.

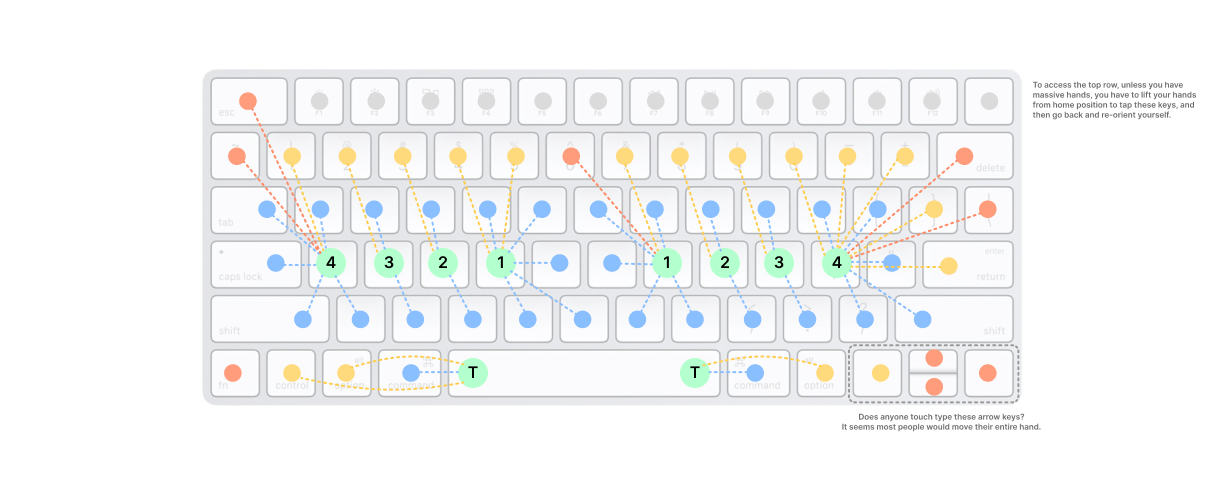

This is a bit dramatic, of course — keyboards were definitely designed for humans — but that design intent is very much affected by the “one key, two symbols” limitation we’ve (🌶️ thoughtlessly) carried over from typewriters. Here’s a keyboard with human hands mapped out for touch typing.

The things that stood out to me:

- 😮 Wow, that’s a lot of keys, and they’re layed out pretty strangely! Maybe it’s okay that I’m having trouble not looking down at the keyboard…

- 🪜 The key stagger is really inconsistent. Like, literally every finger has a subtly different motion it needs to perform. I shouldn’t be so hard on myself while I’m learning to touch type, it makes sense that this muscle memory is difficult to develop.

- 🤦 My right pinky has to cover 12 different keys. Some of the farthest ones, like brackets, are ones I use very often when coding. No wonder I’m having so much trouble touch typing when trying to code.

- 🔁 Clearly I can’t really touch type the arrow keys… can anyone? Surely I have to move my right hand to a different position to access them? But I use them a lot when coding! This sucks. Maybe I should learn

vim? - 🤷 … maybe it’s not my fault I can’t touch type very well, and it’s actually a keyboard design challenge?

With this all in mind, it seems clear that the number of keys on most traditional keyboards is highly influenced by design constraints that no longer exist.

What else could we design for?

The “one key, two symbols” constraint and also the “stagger columns to avoid the typewriter keys sticking” constraint are both self-imposed and outdated.

For me at least, they seem to make typing difficult, with no real benefits to make up for that difficulty. This difficulty feels compounded when trying to type symbols used in coding, many of which were not accounted for at all in traditional typewriter and keyboard design.

Typewriters and keyboards might still look similar… but with a keyboard that has independent switches, when we press a key, or even a whole chord or sequence of keys, we can basically do whatever we want. What if we discarded our self-imposed constraints for a second, and considered what other design goals keyboards are trying to achieve?

Design goals

These are the goals I had in mind when looking for an alternative to the Apple Magic Keyboard I was used to using:

Note: these are very much retroactive articulations of what I’ve eventually settled on as design goals. At the time I was looking for a new keyboard, I felt pretty scattered, aimless, and overwhelmed. But I do feel like I had an inkling of these ideas fermenting in the back of my mind.

- When I type, I want to use my hands comfortably to type symbols I’m familiar with

- The symbols I’m familiar with are the English alphabet, numbers, and the symbols found on a typical keyboard. As cool as it sounds, I don’t want to learn stenotype.

- All the keys should be easy to reach.

- The arrangement of keys should be easy to reason about, and match how my hands work.

- I should be able to feel when my hands are in the right place.

- When I type, I’m trying to focus on something else, not typing. Layout & key layers should feel natural.

"natural"is, of course, very much an opinionated thing- History and apparent flaws aside, the reality is that I’m used to a QWERTY layout. And I still want to be able to type on my laptop keyboard without my brain exploding. Completely re-imaging my keyboard layout will mean it’ll take a long time before things start to feel natural (if they ever do — and it’ll be hard to tell along the way).

- I use keyboard shortcuts a lot. I want to retain those, having to rebuild that muscle memory and layout memory entirely would be really annoying.

- I’ve heard of ergonomic keyboard layouts with four, five, or six layers. Generally these seem to be used to avoid having to press

Shift, or trying to reduce keys down to 34 or less. I am already used to two layers, with theShiftkey providing the second layer. I want to build on this familiarity withShift. Ergonomics for the mind. - At the same time, I know there will need to be a period of adjustment. I want to approach this adjustment progressively — at first, I’ll type English language prose only (cause the alphabet fits easily in 42 keys). Then I’ll try to move up to typing numbers and symbols. Eventually I may be able to confidently touch type all of the symbols I need for coding.

- When I type, I want to avoid looking at the keyboard

- I’m trying to focus on writing something, not on which key to press

- I want something that actively discourages me from looking down

- When I type, I want to have decent posture, and encourage movement

- Forcing myself to sit a certain way doesn’t seem like a good answer

- Something that encourages movement would be nice. I think sometimes I gravitate towards typing on my laptop for this reason - it’s easier to wander around my apartment and sit in different ways with a laptop. Maybe some kinda keyboard design could encourage this?

Rationale for the hardware

As soon as I started researching how I might design a keyboard that meets these needs, I realized there’s already a ton of hardware out there. I definitely went down a bit of a rabbit hole before looking around, and I’m glad I did come up for air earlier rather than later.

Anyways, I eventually came across the 42-key ortholinear, staggered layout, which has been around for a while.

Here’s my rationale for why any split corne-ish keyboard hardware with 42 keys, in aligned columns, with light-weight switches and blank key caps, works nicely (as it relates to the previously stated design goals):

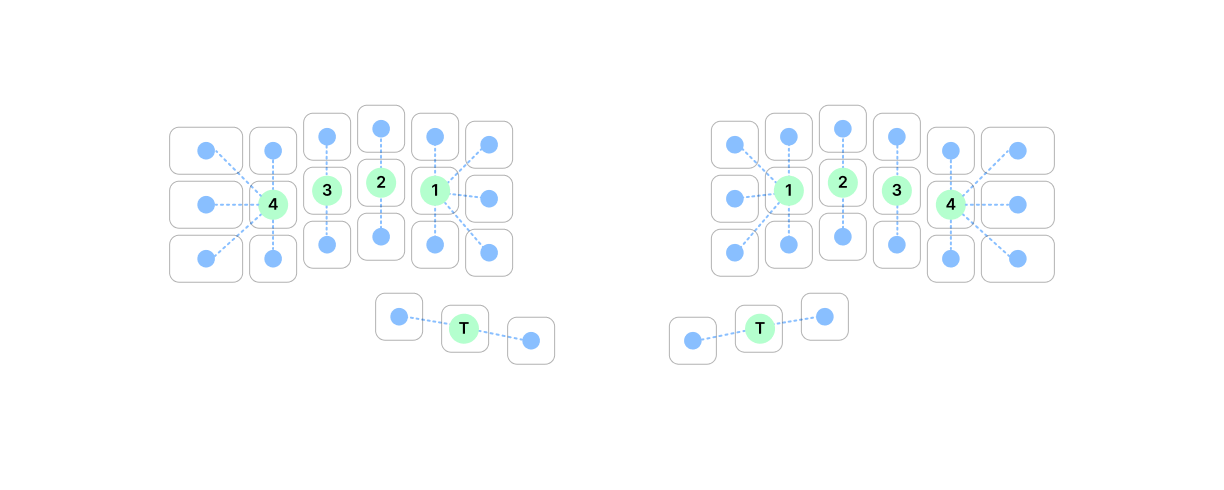

- All the keys are easy to reach

- each finger has to reach a maximum of ~ 1 cm, or one unit on the keyboard grid

- the aligned columns mean the direction of reach aligns well with finger-bending movement. this is in constrast to the wrist-rotating movement required by typewriter-style layouts with misaligned columns, which I find much harder and more straining.

- The physical arrangement of keys makes sense to me

- it’s nice and grid-like, this makes my brain happy

- alignment only varies subtly, and only to match human hands, with slight stagger between columns and a thumb-friendly 3-key bottom row

- Blank keys make it pointless to look down

- Looking down does not feel natural, I want to focus on the work in front of me, on the screen

- When learning a layout, it feels right that the layout should be on a piece of paper taped to my wall or beside my screen, rather than on the keyboard itself. Gets me in the habit of looking up what I’m trying to type, not down at my hands. Eventually I can get rid of the piece of paper.

- Sure, designing 3-layer keycap labels or something fun and decorative could be neat. But then I’d look down at my hands more. The only reason I can think of to design labelled keycaps at this point is if someone needs to use my computer for some weird emergency reason, which is kind of a nonsensical situation (and even if it wasn’t, my laptop can always be undocked and used directly).

- Posture and movement are more intuitive

- For me, split halves have made a more comfortable set of postures, & perhaps more importantly motion between those postures, feel more intuitive.

- Placing the halves shoulder-width apart seems to encourage me to not turn my shoulders in and hunch over the keyboard

- The ability to vary the distance between the halves seems to create a bigger set of similar, but different, and still comfortable typing postures than with a one-piece keyboard

- This larger set of comfortable postures seems to encourage me to move things around a bit during the day, rather than keeping the keyboard in the exact same place

- Keys can be physically easier to press

- Watch a terminally on-their-phone person type out a text. With two fingers and a good deal of practice, we can get not-so-far-off from typing speeds on full-size keyboards. I think touch screens are a factor here, minimizing the effort it takes to type each symbol.

- Light-weight keyboard switches make it much easier to type without your hands getting tired. The switches I like also have a pretty short travel distance, which means the tiniest downward movement of a finger is enough to type a symbol. This takes some getting used to, especially if you’re in the habit of keeping some weight in your fingers even when you’re not actively typing. But for me at least, it’s felt worth it to make the switch (🥁). Light-weight switches also feel like a natural pairing to additional layer keys. With a layout where you can reach all the keys, you’ll use layer modifiers like

Shiftmore often, and the ease of light-weight switches is most noticeable when you have to press multiple keys.

Note: It’s definitely possible to keep your chest open, shoulders back, and to move things around occasionally with a one-piece keyboard. There seem to be a lot of neat & very ergonomic one-piece keyboards out there. I personally find it harder though - I find the inward positioning of my arms usually translates to bringing my shoulders in as well. I also find less point in moving the keyboard around, which in turn means less posture variation, since I can’t do things like vary the distance between keyboard halves.

Rationale for the layout (aka firmware)

Researching layouts was, in many ways, much messier than hardware.

The core difference with small ergonomic keyboard layouts is the concept of multiple layers. In typewriters, the Shift key created a new “layer” of symbols that could be accessed with a single key. In the digital world… well, I guess you take “layers” to an extreme and type every possible symbol with a single key switch, with a really complicated layer setup that distinguishes between long taps, to switch to the next possible symbol, and short taps, to type the symbol.

If typing every possible symbol with a single keyswitch sounds absurd, consider that there have been serious attempts to reduce the number of keyswitches down to ten (one for each finger!) and do all the work with “chording” (pressing multiple keys simultaneously). Consider as well that the fastest typists in the world use “chording” almost exclusively, with a completely different symbol set from the alphabetical one normal typists are used to (this was a huge TIL for me when looking into keyboard layouts). It takes a long time to learn this new symbol system, and these new “chords”, but doing so seems to be the only way for a human to transcribe conversations in real time.

In any case, the point is that “what is the most ergonomic keyboard layout” is an extremely deep rabbit hole of a question. As always, the answer is really dependent on what you’re trying to achieve. The first weirdo keyboard I bought took longer than expected to ship, so I had months to overthink how I wanted the keyboard layout to work. I had some ideas.

But I’m also lazy, so at first I tried the default slash recommended layout for the keyboard I bought. I found it really complicated and discouraging — it didn’t work for me at all. The thought of messing with firmware loading sounded intimidating, and I almost gave up, but ended up deciding that I’d already done so much overthinking that I should at least follow through and learn how to load the firmware.

And it turned out that configuring and loading the firmware was a lot easier than I thought. For keyboards that support QMK (a lot of them!) there’s an online firmware playground and compiler, and a pretty easy-to-use app for flashing the resulting .hex file. After reading some docs, watching a few videos, and revisiting all the overthinking I’d done, I’m pretty happy with the result.

The annotations in the image above go into a bit more detail. I’ve used this QWERTY-ish layout for a few years, across a couple different keyboards, and I’ve managed to learn to touch type. And that includes the arrow keys and all the brackets, which I still think are kind of impossible to reach comfortable on traditional keyboards without having to move away from the home row. So I’m confident that even if it’s not ideal, the QWERTY-ish layout I’ve set up is a decent place for many people to start. It also feels like it’s meeting my design criteria:

- All the symbols are the same, the default layer feels exactly like QWERTY. It started feeling natural for writing prose within a few weeks of regular use.

- The keys feel way easier to reach. Within a few weeks, using layers for brackets and other symbols already felt much more natural than trying to learn the mental and physical gymnastics required to type every kind of bracket using only my right pinky on a traditional keyboard. And things have just gotten easier from there.

- I’ve kept it down to a minimal 3 layers, and have kept each key’s job the same as it was in QWERTY, even if they’ve moved around a bunch. This requires frequent use of the

SYMBOLlayer key and theShiftmodifier key together at the same time, but that combination started to feel like a natural “chord” within the first few weeks of working on the symbol layer. - The arrangement of

Control,⌥ Option, and⌘ Commandkeys has felt right, as it mirrors the Apple keyboards I’m used to. Keyboard shortcuts still feel mostly intuitive. “Mostly” cause shortcuts that involve numbers or symbols took some getting used to. - My posture feels better, and my wrists feel a lot better. There’s a whole other rabbit hole on keyboard positioning and tenting to go down here. In short, I use to think my bad posture at the keyboard was because I was careless or lazy, and if I could just find the perfect overpriced desk chair, that’d fix me. Now I think that using the smushed-together poorly-aligned grid of keys of a traditional keyboard should take more of the blame for anyone’s bad posture at their computer than everything except monitor position. My new favourite thing is sitting on the floor with a wireless keyboard on DIY thing that’s basically just a two-foot-wide monitor stand with a slide-out tray.

- I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how natural it has felt to switch back to a QWERTY layout. Apart from still hating the staggered columns of traditional keyboards, I’ve started actually being able to touch type, even on my laptop keyboard (which is a surprise to me!). I think it’s a little ironic that the only way I could get myself to learn to touch type on a traditional keyboard is by learning to touch type on a very different kind of keyboard.

- The arrow keys being right under my fingers feels like a huge improvement that I didn’t really anticipate. Navigating around text documents feels so much easier. And cause it’s part of the keyboard, not a software thing, it works across any app (take that, the shame I feel for failing to learn

vim!). I’m so sold on the value of easily accessible arrow keys that I made it work on my laptop keyboard as well, with some fancy software that changesi j k lto↑ ← ↓ →when the right-side⌘ Commandkey is pressed.

It was a process

As excited as I am about the looming ergonomic keyboard revolution, and as committed as I am to the cause, I’m not going to pretend it was super easy or really all that fun to have to learn how to type on an unfamiliar and intimidating-looking jumble of poorly soldered and arguably overpriced components.

Even after I emerged from the other end of the weird rabbit holes that seem to be a core part of the custom keyboard community, it took me several months to actually get used to typing.

- I started with short practice sessions, tried to be consistent, but wasn’t that great at it

- It took me several weeks of cycling through trying, giving up, being fascinated and being frustrated before I started to feel at all comfortable

- I had never really touch typed before, and I’m still not sure whether than was a disadvantage (zero familiarity) or an advantage (less to unlearn)

- I tried typing prose and writing out thoughts, which you can get away with on the default layer only

- I found typing prose only at first was great for learning the layout, and getting familiar with the layer keys. I’d just ignore apostrophes (

') & quotation marks (") since these aren’t on the default layer.

- I found typing prose only at first was great for learning the layout, and getting familiar with the layer keys. I’d just ignore apostrophes (

- Once I was a little more comfortable, I started adding in those apostrophes and quotation marks, as well as dashes. Felt like a good way to ease into the

SYMBOLlayer. - In parallel, I started trying out arrow key navigation through the

NAVlayer. Tapping the individual arrow keys on theNAVlayer felt okay to pick up. - Holding

⌥ Optionand using the left & right arrow keys to jump word-to-word rather than character-to-character was new to me, but is now something I do almost constantly. Similarly, holding⌘ Commandand using the left and right arrow keys for beginning and end of line jumping, or up and down for start or end of a document, feel really useful once the arrow keys are a layer away (rather than a reach away). - Coding was really slow at first - in anything substantial, it wasn’t realistic to limit to a specific set of characters, you kind of need everything. It took a while to feel like it was paying off. (At the time I kept switching my layout around though, that might have been part of it). Practice tools:

- I really like the free Typist program for the initial “where the fuck do i move my hands and how hard do I have to press” phase (even if it’s a bit clunky on the UI side)

- I’ve found it especially helpful for numbers and symbols, since it’s very formulated around helping build the initial muscle memory. A lot of other apps I’ve tried seem to skip that foundational work and expect you to jump right into speed drills.

- I like the free keybr.com site for ongoing typing practice.

- Seems great for improving speed and accuracy once you’re kind of comfortable. Doesn’t seem to help build the initial muscle memory, though.

- For a while a played this Steam game called

Epistory. A lot likekeybr.comthough - in my opinion it doesn’t teach anyone to type; it teaches anyone who knows how to type to speed up.